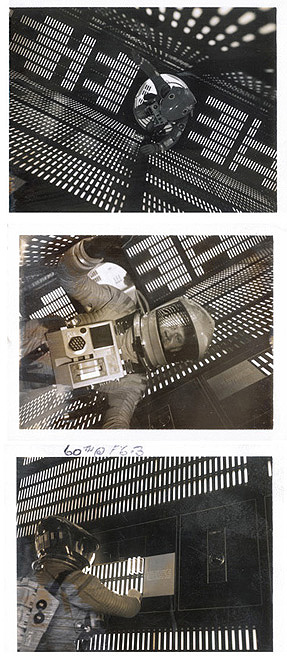

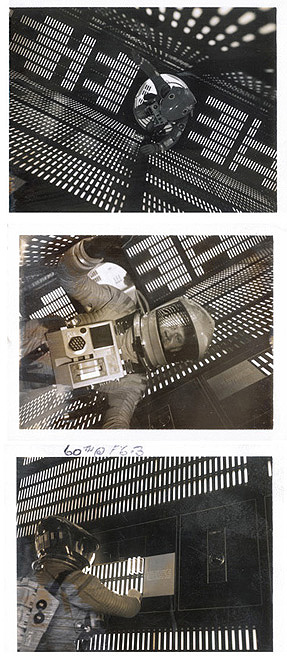

[Original works from the Stanley Kubrick Estate.

Stanley Kubrick and Geoffrey Unsworth developed a system for calculating from the grey tones of b/w Polaroids the right lighting for filming

2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY.]

Update

¬

Subscribe Newsletter

Newsletter no. 15, March 2005

PLEASE NOTE: BECAUSE OF ITS GREAT SUCCESS THE EXHIBITION WAS EXTENDED FOR ANOTHER WEEK TO 18 APRIL!

Dear colleagues and friends:

Stanley Kubrick left to posterity thirteen-or rather twelve publicly accessible-feature films and three short films.

These comprise a small but momentous oeuvre in which each single film takes a specific place and is reference to

years of meticulous preparatory work. In their very own form and effect they can only be properly experienced in

the movie theater. One-rather important-facet of Kubrick's fame constitute films that never made it to the screen:

his never realized projects. To represent them was from the very beginning an important goal and unique potential

of the exhibition and for this we were able to make use of comprehensive material from the Estate.

Many of Kubrick's non-realized film projects date from the 1950s when the film director was still at the beginning

of his career and explored several different directions. One of these projects was

The German Lieutenant, which

focused on a German parachute squad at the end of WWII; another was the western ONE-EYED JACKS, which was finally

directed by Marlon Brando. Kubrick's later film projects are better known, among them the holocaust drama

Aryan

Papers (based on the novel

Wartime Lies by Louis Begley) which was never produced after the release of Steven Spielberg's

SCHINDLER'S LIST. Another project that was long in the making was A.I. ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE, realized after Kubrick's

death by Steven Spielberg whom Kubrick had already offered the director's chair.

The most famous project however was

Napoleon, which "still fascinates as a legend of film history, as missing link

in Kubrick's oeuvre" (Eva-Maria Magel). In this long-time favourite yet never realized endeavor the film director's

view of the world, his personality and his work methods symbolically fused. Therefore the last great event of the

Berlin exhibition is devoted to this project: the first-ever public reading from Kubrick's Napoleon-script with an

introduction by Eva-Maria Magel who has done intensive research on the subject at the Estate and published some of

her insights in her catalogue entry "The best movie (n)ever made". The finissage will take place on 14 April at the

Martin-Gropius-Bau. Please look for more details in the upcoming newsletter.

1. This month's object: the Napoleon card index

Kubrick's research effort for the Napoleon project by far exceeded the customarily extensive preparations of all his

other, finished films. The most intensive work phase took place in the years 1968 and 1969 when he wrote his screenplay.

He had historians as consultants, especially the Napoleon expert Felix Markham whom he took under contract and of whom

he inquired the most minute details of Napoleon's key experiences and daily habits. Starting in June 1968 Kubrick had

Markham's students at Oxford University put together dossiers on all important persons surrounding Napoleon. Thus a

complex filing system was created which listed dates and names, but also information such as the weather during a

certain battle. The color tabs on the cards represent different people. The imposing card index box bears witness to

Kubrick's obsession with details and his liking for cataloguing systems. All this can be marveled at-and partly looked

into-in the exhibition. Moreover books from Kubrick's comprehensive Napoleon library have been included in the display.

On this research was based the script version of 1969 which comprised 150 pages. Based on this the film would have had

a duration of three hours. The monumental project failed, however, when first MGM and then United Artists withdrew from

financing the production after the box office failure of Sergej Bondartschuk's Napoleon-film WATERLOO (1970) and due

to the general trend for less monumental productions in "New Hollywood". As a consequence Kubrick turned to A CLOCKWORK ORANGE,

the adaptation of the controversial novel by Anthony Burgess (at the same time he suggested to him to write about Napoleon,

and in 1974 Burgess actually published the

Napoleon Symphony, an allusion to Beethoven's symphony "Eroica"). Next Kubrick

filmed BARRY LYNDON based on the novel of the same name by Thackeray, a project that made use of much thematic and

technical preparatory work for

Napoleon (among others the candle light shots for which he had done experiments as

early as 1968, at that time without the light sensitive Zeiss-objective). Kubrick here shifted his gaze from a

pivotal historical figure to a fictional minor character in the 18th century. Yet his fascination with Napoleon

never left him, as Jan Harlan explains: "Napoleon represented for him the worldly genius that at the same time

failed". Until Kubrick's death there were rumors as to whether he would yet realize this film; today there

remains only the speculation as to whether this project too might be finished by another film director.

2. Brief portrait: Andrew Birkin

Napoleon marks the start of the collaboration of Kubrick and his brother-in-law, Jan Harlan, who from then on

became his closest assistant. Harlan went on location hunts in Rumania and Yugoslavia and negotiated with local

authorities. Somebody else traveled for research related to

Napoleon: Andrew Birkin who had started as an intern

at 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY and later turned film director and scriptwriter himself. He is the older brother of actress

Jane Birkin and was born in London in 1945. At age sixteen he dropped out of school and worked as a courier at the

London office of 20th Century Fox. Between 1963 and 1970 he assisted in various productions, eventually in 2001:

A SPACE ODYSSEY where he, according to his recollections, kept busy making copies and coffee. He attracted Kubrick's

attention when he suggested a British location for the filming of the "Dawn of Man"-sequence, even though this idea

was later discarded. Yet Kubrick was impressed with Birkin's geographical knowledge and his eye for motives and when

the decision was made to take pictures for the front projection in South Africa, Kubrick sent Birkin as photographer.

In this capacity Kubrick also wanted him for the Napoleon project: he was to visit authentic locations where Napoleon

had been and to take photographs. Birkin, who in the meantime had collaborated in the Beatles' "Magical Mystery Tour",

traveled to Russia, Austria, Rumania, Italy and France in 1968. From his travels he brought back to Kubrick, apart

from countless photos and other things, soil from Waterloo and a copy of Napoleon's death mask. There was no further

collaboration after that because the project was put on hold and Birkin pursued his own projects.

Photo above: Location research photo taken by Andrew Birkin, Chateau of Fontainebleau

In the following years Birkin wrote scripts for television and film, among others for the mini-series on Peter-Pan-inventor

J.M. Barrie titled THE LOST BOYS (1978) and later for THE NAME OF THE ROSE (1986). With his debut as a director in

1988 he realized, curiously, an earlier project stemming from Kubrick: THE BURNING SECRET, the adaptation of Stefan

Zweig's novella

Brennendes Geheimnis. Birkin directed two other films: SALT ON OUR SKIN (1991) and THE CEMENT GARDEN (1992)

with his niece Charlotte Gainsbourg as leading actress. The film was elected best film at the Berlin Film Festival.

Most recently Birkin collaborated with Luc Besson on the script for JEANNE D'ARC (1998) and with German film director

Tom Tykwer on the adaptation of Patrick Süskind's

The Perfume, which is still in production. The topic Napoleon,

which initially barely interested Birkin, has kept up with him as well: twenty years after his travels he wrote his

own screenplay, which has not been realized either. For an extensive interview (albeit in German) with him, please

read: Rolf Thissen.

Stanley Kubrick - der Regisseur als Architekt, Munich 1999.

3. Review of events

Eva-Maria Magel and Ronny Loewy respectively presented the projects

Napoleon and

Aryan Papers on 16 February during

the International Berlin Film Festival (Berlinale) at the Urania. These and other events concerned with Kubrick, who

was the focus of the Berlinale Retrospective, were well frequented-as was the exhibition. Visitor numbers kept rising

and on 18 February we welcomed the 25,000th visitor and by now we have reached almost 50,000.

Three weeks after the Berlin Film Festival, on 5 March, the workshop "Moving Spaces - Aspekte des Labyrinthischen",

organized in collaboration with the Einsteinforum and the Filmmuseum Berlin, took place. Speakers were Jan Harlan, the

American film scholar Claudia Gorbman and theater studies expert Hans-Thies Lehmann. They addressed the use Kubrick

made of space and architecture in his films as well as of music.

¬ drucken

The most famous project however was Napoleon, which "still fascinates as a legend of film history, as missing link

in Kubrick's oeuvre" (Eva-Maria Magel). In this long-time favourite yet never realized endeavor the film director's

view of the world, his personality and his work methods symbolically fused. Therefore the last great event of the

Berlin exhibition is devoted to this project: the first-ever public reading from Kubrick's Napoleon-script with an

introduction by Eva-Maria Magel who has done intensive research on the subject at the Estate and published some of

her insights in her catalogue entry "The best movie (n)ever made". The finissage will take place on 14 April at the

Martin-Gropius-Bau. Please look for more details in the upcoming newsletter.

The most famous project however was Napoleon, which "still fascinates as a legend of film history, as missing link

in Kubrick's oeuvre" (Eva-Maria Magel). In this long-time favourite yet never realized endeavor the film director's

view of the world, his personality and his work methods symbolically fused. Therefore the last great event of the

Berlin exhibition is devoted to this project: the first-ever public reading from Kubrick's Napoleon-script with an

introduction by Eva-Maria Magel who has done intensive research on the subject at the Estate and published some of

her insights in her catalogue entry "The best movie (n)ever made". The finissage will take place on 14 April at the

Martin-Gropius-Bau. Please look for more details in the upcoming newsletter.  Kubrick's research effort for the Napoleon project by far exceeded the customarily extensive preparations of all his

other, finished films. The most intensive work phase took place in the years 1968 and 1969 when he wrote his screenplay.

He had historians as consultants, especially the Napoleon expert Felix Markham whom he took under contract and of whom

he inquired the most minute details of Napoleon's key experiences and daily habits. Starting in June 1968 Kubrick had

Markham's students at Oxford University put together dossiers on all important persons surrounding Napoleon. Thus a

complex filing system was created which listed dates and names, but also information such as the weather during a

certain battle. The color tabs on the cards represent different people. The imposing card index box bears witness to

Kubrick's obsession with details and his liking for cataloguing systems. All this can be marveled at-and partly looked

into-in the exhibition. Moreover books from Kubrick's comprehensive Napoleon library have been included in the display.

Kubrick's research effort for the Napoleon project by far exceeded the customarily extensive preparations of all his

other, finished films. The most intensive work phase took place in the years 1968 and 1969 when he wrote his screenplay.

He had historians as consultants, especially the Napoleon expert Felix Markham whom he took under contract and of whom

he inquired the most minute details of Napoleon's key experiences and daily habits. Starting in June 1968 Kubrick had

Markham's students at Oxford University put together dossiers on all important persons surrounding Napoleon. Thus a

complex filing system was created which listed dates and names, but also information such as the weather during a

certain battle. The color tabs on the cards represent different people. The imposing card index box bears witness to

Kubrick's obsession with details and his liking for cataloguing systems. All this can be marveled at-and partly looked

into-in the exhibition. Moreover books from Kubrick's comprehensive Napoleon library have been included in the display.  On this research was based the script version of 1969 which comprised 150 pages. Based on this the film would have had

a duration of three hours. The monumental project failed, however, when first MGM and then United Artists withdrew from

financing the production after the box office failure of Sergej Bondartschuk's Napoleon-film WATERLOO (1970) and due

to the general trend for less monumental productions in "New Hollywood". As a consequence Kubrick turned to A CLOCKWORK ORANGE,

the adaptation of the controversial novel by Anthony Burgess (at the same time he suggested to him to write about Napoleon,

and in 1974 Burgess actually published the Napoleon Symphony, an allusion to Beethoven's symphony "Eroica"). Next Kubrick

filmed BARRY LYNDON based on the novel of the same name by Thackeray, a project that made use of much thematic and

technical preparatory work for Napoleon (among others the candle light shots for which he had done experiments as

early as 1968, at that time without the light sensitive Zeiss-objective). Kubrick here shifted his gaze from a

pivotal historical figure to a fictional minor character in the 18th century. Yet his fascination with Napoleon

never left him, as Jan Harlan explains: "Napoleon represented for him the worldly genius that at the same time

failed". Until Kubrick's death there were rumors as to whether he would yet realize this film; today there

remains only the speculation as to whether this project too might be finished by another film director.

On this research was based the script version of 1969 which comprised 150 pages. Based on this the film would have had

a duration of three hours. The monumental project failed, however, when first MGM and then United Artists withdrew from

financing the production after the box office failure of Sergej Bondartschuk's Napoleon-film WATERLOO (1970) and due

to the general trend for less monumental productions in "New Hollywood". As a consequence Kubrick turned to A CLOCKWORK ORANGE,

the adaptation of the controversial novel by Anthony Burgess (at the same time he suggested to him to write about Napoleon,

and in 1974 Burgess actually published the Napoleon Symphony, an allusion to Beethoven's symphony "Eroica"). Next Kubrick

filmed BARRY LYNDON based on the novel of the same name by Thackeray, a project that made use of much thematic and

technical preparatory work for Napoleon (among others the candle light shots for which he had done experiments as

early as 1968, at that time without the light sensitive Zeiss-objective). Kubrick here shifted his gaze from a

pivotal historical figure to a fictional minor character in the 18th century. Yet his fascination with Napoleon

never left him, as Jan Harlan explains: "Napoleon represented for him the worldly genius that at the same time

failed". Until Kubrick's death there were rumors as to whether he would yet realize this film; today there

remains only the speculation as to whether this project too might be finished by another film director.  In this capacity Kubrick also wanted him for the Napoleon project: he was to visit authentic locations where Napoleon

had been and to take photographs. Birkin, who in the meantime had collaborated in the Beatles' "Magical Mystery Tour",

traveled to Russia, Austria, Rumania, Italy and France in 1968. From his travels he brought back to Kubrick, apart

from countless photos and other things, soil from Waterloo and a copy of Napoleon's death mask. There was no further

collaboration after that because the project was put on hold and Birkin pursued his own projects.

Photo above: Location research photo taken by Andrew Birkin, Chateau of Fontainebleau

In this capacity Kubrick also wanted him for the Napoleon project: he was to visit authentic locations where Napoleon

had been and to take photographs. Birkin, who in the meantime had collaborated in the Beatles' "Magical Mystery Tour",

traveled to Russia, Austria, Rumania, Italy and France in 1968. From his travels he brought back to Kubrick, apart

from countless photos and other things, soil from Waterloo and a copy of Napoleon's death mask. There was no further

collaboration after that because the project was put on hold and Birkin pursued his own projects.

Photo above: Location research photo taken by Andrew Birkin, Chateau of Fontainebleau